This tutorial serves as a very short and quick summary of the first few chapters of TAPL. Huge thanks to the ##dependent@freenode community (pgiarrusso, lyxia, mietek, …) for clearing all my questions, which provided a good sense of the design of such systems.

1. Untyped simple language

1.1. Syntax

Our syntax, per BNF is defined as follows:

<term> ::= <bool> | <num> | If <bool> Then <expr> Else <expr> | <arith>

<bool> ::= T | F | IsZero <num>

<num> ::= O

<arith> ::= Succ <num> | Pred <num>

For simplicity, we merge all them together in a single Term.

data Term =

T

| F

| O

| IfThenElse Term Term Term

| Succ Term

| Pred Term

| IsZero Term

deriving (Show, Eq)

1.2. Inference rules (evaluator)

The semantics we use here are based on so called small-step style, which state how a term is rewritten to a specific value, written  . In contrast, big-step style states how a specific term evaluates to a final value, written

. In contrast, big-step style states how a specific term evaluates to a final value, written  .

.

Evaluation of a term is just pattern matching the inference rules. Given a term, it should produce a term:

eval :: Term -> Term

The list of inference rules:

| Name |

Rule |

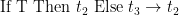

| E-IfTrue |

|

| E-IfFalse |

|

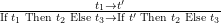

| E-If |

|

| E-Succ |

|

| E-PredZero |

|

| E-PredSucc |

|

| E-Pred |

|

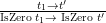

| E-IszeroZero |

|

| E-IszeroSucc |

|

| E-IsZero |

|

As an example, the rule E-IfTrue written using big-step semantics would be  .

.

Given the rules, by pattern matching them we will reduce terms. Implementation in Haskell is mostly “copy-paste” according to the rules:

eval (IfThenElse T t2 t3) = t2

eval (IfThenElse F t2 t3) = t3

eval (IfThenElse t1 t2 t3) = let t' = eval t1 in IfThenElse t' t2 t3

eval (Succ t1) = let t' = eval t1 in Succ t'

eval (Pred O) = O

eval (Pred (Succ k)) = k

eval (Pred t1) = let t' = eval t1 in Pred t'

eval (IsZero O) = T

eval (IsZero (Succ t)) = F

eval (IsZero t1) = let t' = eval t1 in IsZero t'

eval _ = error "No rule applies"

1.3. Conclusion

As an example, evaluating the following:

Main> eval $ Pred $ Succ $ Pred O

Pred O

Corresponds to the following inference rules:

----------- E-PredZero

pred O -> O

----------------------- E-Succ

succ (pred O) -> succ O

------------------------------------- E-Pred

pred (succ (pred O)) -> pred (succ O)

However, if we do:

Main> eval $ IfThenElse O O O

*** Exception: No rule applies

It’s type-checking time!

2. Typed simple language

2.1. Type syntax

In addition to the previous syntax, we create a new one for types, so per BNF it’s defined as follows:

<type> ::= Bool | Nat

In Haskell:

data Type =

TBool

| TNat

2.2. Inference rules (type)

Getting a type of a term expects a term, and either returns an error or the type derived:

typeOf :: Term -> Either String Type

Next step is to specify the typing rules.

| Name |

Rule |

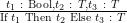

| T-True |

|

| T-False |

|

| T-Zero |

|

| T-If |

|

| T-Succ |

|

| T-Pred |

|

| T-IsZero |

|

Code in Haskell:

typeOf T = Right TBool

typeOf F = Right TBool

typeOf O = Right TNat

typeOf (IfThenElse t1 t2 t3) =

case typeOf t1 of

Right TBool ->

let t2' = typeOf t2

t3' = typeOf t3 in

if t2' == t3'

then t2'

else Left "Types mismatch"

_ -> Left "Unsupported type for IfThenElse"

typeOf (Succ k) =

case typeOf k of

Right TNat -> Right TNat

_ -> Left "Unsupported type for Succ"

typeOf (Pred k) =

case typeOf k of

Right TNat -> Right TNat

_ -> Left "Unsupported type for Pred"

typeOf (IsZero k) =

case typeOf k of

Right TNat -> Right TBool

_ -> Left "Unsupported type for IsZero"

2.3. Conclusion

Going back to the previous example, we can now “safely” evaluate (by type-checking first), depending on type-check results:

Main> typeOf $ IfThenElse O O O

Left "Unsupported type for IfThenElse"

Main> typeOf $ IfThenElse T O (Succ O)

Right TNat

Main> typeOf $ IfThenElse F O (Succ O)

Right TNat

Main> eval $ IfThenElse T O (Succ O)

O

Main> eval $ IfThenElse F O (Succ O)

Succ O

3. Environments

Our neat language supports evaluation and type checking, but does not allow for defining constants. To do that, we will need kind of an environment which will hold information about constants.

type TyEnv = [(String, Type)] -- Type env

type TeEnv = [(String, Term)] -- Term env

We also extend our data type to contain TVar for defining variables, and meanwhile also introduce the Let ... in ... syntax:

data Term =

...

| TVar String

| Let String Term Term

Here are the rules for variables:

| Name |

Rule |

| Add binding |

|

| Retrieve binding |

|

Haskell definitions:

addType :: String -> Type -> TyEnv -> TyEnv

addType varname b env = (varname, b) : env

getTypeFromEnv :: TyEnv -> String -> Maybe Type

getTypeFromEnv [] _ = Nothing

getTypeFromEnv ((varname', b) : env) varname = if varname' == varname then Just b else getTypeFromEnv env varname

Analogously for terms:

addTerm :: String -> Term -> TeEnv -> TeEnv

addTerm varname b env = (varname, b) : env

getTermFromEnv :: TeEnv -> String -> Maybe Term

getTermFromEnv [] _ = Nothing

getTermFromEnv ((varname', b) : env) varname = if varname' == varname then Just b else getTermFromEnv env varname

3.1. Inference rules (evaluator)

At this point we stop giving mathematical inference rules, but it’s a good homework if you want to do it 🙂

eval' is exactly the same as eval, with the following additions:

1. New parameter (the environment) to support retrieval of values for constants

2. Pattern matching for the new Let ... in ... syntax

eval' :: TeEnv -> Term -> Term

eval' env (TVar v) = case getTermFromEnv env v of

Just ty -> ty

_ -> error "No var found in env"

eval' env (Let v t t') = eval' (addTerm v (eval' env t) env) t'

We will modify IfThenElse slightly to allow for evaluating variables:

> eval' env (IfThenElse T t2 t3) = eval' env t2

> eval' env (IfThenElse F t2 t3) = eval' env t3

> eval' env (IfThenElse t1 t2 t3) = let t' = eval' env t1 in IfThenElse t' t2 t3

Copy-pasting the others:

eval' env (Succ t1) = let t' = eval' env t1 in Succ t'

eval' _ (Pred O) = O

eval' _ (Pred (Succ k)) = k

eval' env (Pred t1) = let t' = eval' env t1 in Pred t'

eval' _ (IsZero O) = T

eval' _ (IsZero (Succ t)) = F

eval' env (IsZero t1) = let t' = eval' env t1 in IsZero t'

Also since we modified IfThenElse to recursively evaluate, we also need to consider base types:

eval' _ T = T

eval' _ F = F

eval' _ O = O

3.2. Inference rules (type)

typeOf' is exactly the same as typeOf, with the only addition to support env (for retrieval of types for constants in an env) and the new let syntax.

typeOf' :: TyEnv -> Term -> Either String Type

typeOf' env (TVar v) = case getTypeFromEnv env v of

Just ty -> Right ty

_ -> Left "No type found in env"

typeOf' _ T = Right TBool

typeOf' _ F = Right TBool

typeOf' _ O = Right TNat

typeOf' env (IfThenElse t1 t2 t3) =

case typeOf' env t1 of

Right TBool ->

let t2' = typeOf' env t2

t3' = typeOf' env t3 in

if t2' == t3'

then t2'

else Left $ "Type mismatch between " ++ show t2' ++ " and " ++ show t3'

_ -> Left "Unsupported type for IfThenElse"

typeOf' env (Succ k) =

case typeOf' env k of

Right TNat -> Right TNat

_ -> Left "Unsupported type for Succ"

typeOf' env (Pred k) =

case typeOf' env k of

Right TNat -> Right TNat

_ -> Left "Unsupported type for Pred"

typeOf' env (IsZero k) =

case typeOf' env k of

Right TNat -> Right TBool

_ -> Left "Unsupported type for IsZero"

typeOf' env (Let v t t') = case typeOf' env t of

Right ty -> typeOf' (addType v ty env) t'

_ -> Left "Unsupported type for Let"

Some examples:

Main> let termEnv = addTerm "a" O $ addTerm "b" (Succ O) $ addTerm "c" F []

Main> let typeEnv = addType "a" TNat $ addType "b" TNat $ addType "c" TBool []

Main> let e = IfThenElse T (TVar "a") (TVar "b") in (eval' termEnv e, typeOf' typeEnv e)

(O,Right TNat)

Main> let e = IfThenElse T (TVar "a") (TVar "c") in (eval' termEnv e, typeOf' typeEnv e)

(O,Left "Type mismatch between Right TNat and Right TBool")

Main> let e = IfThenElse T F (TVar "c") in (eval' termEnv e, typeOf' typeEnv e)

(F,Right TBool)

Main> let e = (Let "y" (TVar "a") (Succ (TVar "y"))) in eval' e termEnv

Succ O

Main> let e = (Let "y" (TVar "a") (Succ (TVar "y"))) in typeOf' e typeEnv

Right TNat

4. Product and union

Products and unions are awesome, so we will implement them! We extend the value constructors as follows:

data Term =

...

| Pair Term Term

| EitherL Term

| EitherR Term

…and for the type checker:

data Type =

...

| TyVar String -- constants, use later

| TyPair Type Type -- pairs, use later

| TyEither Type Type -- sum, use later

We add handling to the evaluator:

eval' _ (Pair a b) = Pair a b

eval' env (EitherL a) = eval' env a

eval' env (EitherR a) = eval' env a

…and the type checker:

> typeOf' env (Pair a b) =

> let a' = typeOf' env a

> b' = typeOf' env b in

> case a' of

> Right ta -> case b' of

> Right tb -> Right $ TyPair ta tb

> Left _ -> Left "Unsupported type for Pair"

> Left _ -> Left "Unsupported type for Pair"

> typeOf' env (EitherL a) = case (typeOf' env a) of

> Right t -> Right $ TyEither t (TyVar "x")

> _ -> Left "Unsupported type for EitherL"

> typeOf' env (EitherR a) = case (typeOf' env a) of

> Right t -> Right $ TyEither (TyVar "x") t

> _ -> Left "Unsupported type for EitherR"

Where TyVar "x" represents a polymorphic variable, and is unhandled since our system has no real support for polymorphism.

Main> let e = IfThenElse T (Pair (TVar "a") (TVar "b")) O in (eval' termEnv e, typeOf' typeEnv e)

(Pair (TVar "a") (TVar "b"),Left "Type mismatch between Right (TyPair TNat TNat) and Right TNat")

Main> let e = IfThenElse T (Pair (TVar "a") (TVar "b")) (Pair O O) in (eval' termEnv e, typeOf' typeEnv e)

(Pair (TVar "a") (TVar "b"),Right (TyPair TNat TNat))

Main> eval' termEnv (EitherL (TVar "a"))

O

Main> typeOf' typeEnv (EitherL (TVar "a"))

Right (TyEither TNat (TyVar "x"))

However, note for union, we have the following:

Main> let e = IfThenElse T (EitherL O) (EitherR F) in (eval' termEnv e, typeOf' typeEnv e)

(O,Left "Type mismatch between Right (TyEither TNat (TyVar \"x\")) and Right (TyEither TBool (TyVar \"x\"))")

This can be fixed by implementing a new function typeEq, that extends the Eq of Type, which would always pass the check for our fake polymorphic variable. It could look something like:

typeEq :: Type -> Type -> Bool

typeEq (TyEither x (TyVar "x")) (TyEither (TyVar "x") y) = True

typeEq x y = x == y

5. Conclusion

The evaluator and the type checker almost live in two separate worlds — they do two separate tasks. If we want to ensure the evaluator will produce the correct results, the first thing is to assure that the type-checker returns no error. It was really interesting to understand the mechanism of type-checking in-depth 🙂

Another interesting observation is how pattern matching the data type is similar to the hypothesis part of the inference rules. The relationship is due to the Curry-Howard isomorphism. When we have a formula  (a implies b), and pattern match on a, it’s as if we assumed a and need to show b.

(a implies b), and pattern match on a, it’s as if we assumed a and need to show b.

TAPL starts with untyped lambda calculus and proceeds to typed lambda calculus, but is focusing only on type environment, while leaving the variables environment. While this is a good approach, I feel producing a system like in this tutorial is a good first step before jumping to lambda calculus.

My next steps are to finish reading TAPL, and continue playing with toy languages. The code used in this tutorial is available as a literate Haskell file. I also had some fun with De Bruijn index.

Bonus: Haskell is based on the typed lambda calculus, while Lisp is based on the untyped lambda calculus. It is interesting to note the difference in writing a type-checker in the typed lambda calculus vs the untyped one. Here’s an implementation in Lisp for sections 1 and 2.