According to Wikipedia, the bisection method in mathematics is a root-finding method that repeatedly bisects an interval and then selects a subinterval in which a root must lie for further processing. We can use this method to find zeroes of some continuous function.

Finding zeroes of a function is a very useful concept in practice. Since the function can be almost anything, this means that we can solve about any equality.

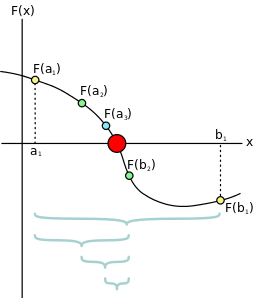

For a given continuous function , and an interval

, where

and

(that is, the function changes sign for some value in that interval), the algorithm thus tries to minimize

such that

, where

.

The algorithm is as follows:

- Set interval

- Calculate

- If

is sufficiently small, stop

- Else if

, then set

- Else, set

- If

- Goto 1

As always, definitions are best understood with examples, so we’ll give a few examples.

Example 1: Approximating square root

We will start by approximating the value of . The function we want to find zero for is then

, since

. We have that

, thus our interval is

.

Let's apply the algorithm a few times now:

| a | b | |

| 2 | 4 | |

| 2 | 3 | |

| 2 | 2.5 | |

| 2 | 2.25 | |

| 2.125 | 2.25 | |

| 2.1875 | 2.25 |

So, 2.21875 is a close approximation of . We can make it even closer by applying the algorithm a couple of more times.

Example 2: Finding a bad commit in a sequence of commits

As a second example, let’s imagine a function that will represent a bunch of Git commits, where one of the commits are bad. Let’s pick such a function at random, maybe . We will also agree that the function returns a value greater than 0 if the software is functioning at that point of commit, and a value less than or equal to 0 otherwise.

How will you find the bad commit? Brute-force or linear search is one way, but it may not be as efficient as bisecting. You can graph the function and look at its zeroes, but that’s a bit cheating, and usually impossible to do in practice with git-bisect since we cannot cover all predicates (in which case

here is “software is functioning”), and thus cannot construct a graph of all such functions w.r.t commits. Since we’re cool, we’ll use the bisection method.

Let’s start at random, knowing at least one good and one bad commit. Maybe picking the interval is a good start. We have that

.

Our task is to find which commit caused the software to break. Let's apply the same algorithm.

| a | b | |

| 50 | 10 | |

| 50 | 30 | |

| 40 | 30 |

So, in just 3 steps we found that the bad commit was 35.

Git-bisect

git-bisect is a very useful command. Given a sequence of commits, it allows you to find a commit that satisfies some property.

The way bisect works is that it will find zeroes of the function . So, given an interval of commits

, the function will return

such that

holds for it.

The fastest way to do that is to use bisection, which we explained earlier. Git uses good and bad for bisecting left and right.

For example, let’s assume we have the following setup:

bor0@boro:~$ git init Initialized empty Git repository in /Users/bor0/.git/ bor0@boro:~$ echo "Hello World!" > test.txt bor0@boro:~$ git add test.txt && git commit -m "First commit" [master (root-commit) faf3b15] First commit 1 file changed, 1 insertion(+) create mode 100644 test.txt bor0@boro:~$ echo "Hello Worldd!" >> test.txt bor0@boro:~$ git add test.txt && git commit -m "Second commit" [master c9b527b] Second commit 1 file changed, 1 insertion(+) bor0@boro:~$ echo "Hello World!" >> test.txt bor0@boro:~$ git add test.txt && git commit -m "Third commit" [master 8d28e4a] Third commit 1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

Now, if we check the contents of the file:

bor0@boro:~$ cat test.txt Hello World! Hello Worldd! Hello World!

For the sake of this demo, let’s assume the the only acceptable string in a list of strings is “Hello World!”. So the latest commit is now broken. In order to find which commit broke this, we can use bisect as follows:

bor0@boro:~$ git bisect start

bor0@boro:~$ git bisect bad 8d28e4a

bor0@boro:~$ git bisect good faf3b15

Bisecting: 0 revisions left to test after this (roughly 0 steps)

[c9b527bbd44542fb7d69df15ce82919055b36578] Second commit

bor0@boro:~$ cat test.txt

Hello World!

Hello Worldd!

bor0@boro:~$ git bisect bad

c9b527bbd44542fb7d69df15ce82919055b36578 is the first bad commit

commit c9b527bbd44542fb7d69df15ce82919055b36578

Author: Boro Sitnikovski <buritomath@gmail.com>

Date: Sun Oct 21 20:10:44 2018 +0200

Second commit

:100644 100644 980a0d5f19a64b4b30a87d4206aade58726b60e3 0c5b693e0f16f325e967f6482d4f9fe02159472b M test.txt

bor0@boro:~$

It was easy in this case, since we had 3 commits. But if you had 1000 commits, it would only take about 10 good or bad choices, which is cool.

So our property was , and so our function

(the result of

git bisect) returned c9b527bbd44542fb7d69df15ce82919055b36578, the first commit where the property was satisfied.

As a conclusion, it’s interesting to think that we’re actually finding a zero of a function when we use git-bisect 🙂

Bonus: Example implementation in Scheme:

(define (bisect f iterations low high)

(letrec ([approx (/ (+ low high) 2)]

[computed (f approx)])

(cond ((zero? iterations) approx)

((> computed 0) (bisect f (- iterations 1) low approx))

(else (bisect f (- iterations 1) approx high)))))

Interacting with it:

> (bisect (lambda (x) (- (* x x) 5)) 50 2.0 4) 2.236067977499789