You can find some of the examples that I did when I was experimenting with Haskell on my GitHub project https://github.com/bor0/haskellfun.

These examples are experimental stuff based on the LYAH book.

life, mathematics, programming

You can find some of the examples that I did when I was experimenting with Haskell on my GitHub project https://github.com/bor0/haskellfun.

These examples are experimental stuff based on the LYAH book.

Today I had this strange experience regarding eta-reduction and Haskell’s laziness.

I was trying out some memoization examples from http://www.haskell.org/haskellwiki/Memoization, so I spent some time specifically on:

memoized_fib :: Int -> Integer

memoized_fib = (map fib [0 ..] !!)

where fib 0 = 0

fib 1 = 1

fib n = memoized_fib (n-2) + memoized_fib (n-1)

So I ran this example in Haskell and everything worked fine!

In order to understand what this function does, I started to explore it around and eventually I rewrote the second line as:

memoized_fib x = (map fib [0 ..] !!) x

However, be careful when you are doing something like this! By removing the eta-reduction on this kind of functions, Haskell evaluates x on every iteration!

So the memoized_fib worked as slow as slow_fib.

As strange and as non-intuitive as this may sound, eta-reduction *can* change the overall behaviour of a function.

This is my attempt of re-implementing the standard words function:

isSpace' x = x == ' '

removeFirst [] = []

removeFirst (x:xs) = if isSpace' x then removeFirst xs else (x:xs)

break' p xs = break'' p xs []

where

break'' p (x:xs) ys = if (p x) then (ys, x:xs) else break'' p xs (ys ++ [x])

break'' _ [] ys = (ys, "")

words' x = words'' ("", x)

where

words'' (_, "") = []

words'' (a, b) = [q] ++ words'' (q, r)

where

q = fst (break' isSpace' b)

r = removeFirst (snd (break' isSpace' b))

The Probably Monad is same as the Maybe Monad, so this is how I had it defined:

data Probably x = Nope | Kinda x deriving (Show)

instance Monad Probably where

Kinda x >>= f = f x

Nope >>= f = Nope

return = Kinda

add x y = x >>= (\x -> y >>= (\y -> return (x + y)))

-- Example: add (add (Kinda 1) (Kinda 2)) (Kinda 4)

Proof:

1. Left identity:

return a >>= f ≡ f a

“return a” by definition is “Kinda a”, and so the bind operator is defined as “Kinda a >>= f ≡ f a”.

So with these two definitions, we have shown that “return a >>= f ≡ f a”.

2. Right identity:

m >>= return ≡ m

If we let m equal “Kinda n”, then we have “Kinda n >>= return ≡ Kinda n”, but by definition of the binding operator,

we have that “Kinda n >>= return = return n”, and so “return n”. So, by definition of return, we have “Kinda n”, which is m.

3. Associativity:

(m >>= f) >>= g ≡ m >>= (\x -> f x >>= g)

If we let m equal “Kinda n”, then we have:

LHS: (Kinda n >>= f) >>= g ≡ (f n) >>= g

RHS: Kinda n >>= (\x -> f x >>= g) ≡ (\x -> f x >>= g) n ≡ f n >>= g

I was looking at Wikipedia’s article regarding Monoids, and decided that it was interesting to make a post regarding the section “Monoids in Computer Science” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monoid#Monoids_in_computer_science.

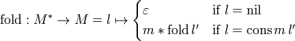

So there they have posted this formula:

And let’s also take a look at Haskell’s definition for fold:

(>>>) = (++)

fold [] = []

fold (m:l') = m >>> (fold l')

Notice the relation between the formulas? Just replace >>> with *, and there you have it!

Regarding the types, in Haskell we have:

*Main> :t fold

fold :: [[a]] -> [a]

And in Mathematics, we have:

fold: M* -> M

The star here represents Kleene’s star, and it is defined to be all concatenations on the elements of the set M, including the empty string (). Example, if M = {a, b} then M* = {(), (a), (b), (a,a), (a,b), (b,b), (b,a), (a,b,a), …}. So what this means is, that if we have M defined as list of integers, then M* would be list of list of integers (which is the result of list concatenation of the elements of M).

And what is fold? Well, fold basically takes a Monoid and applies its operation. Now that we have these two formulas, we can show how fold operates on a Monoid.

Let’s consider the Monoid M ([Int], ++, []). First, to prove that this triple makes a monoid, we must first take a look at the definition of ++:

[] ++ ys = ys

(x:xs) ++ ys = x : (xs ++ ys) (*)

1. Closure

Namely, the (++) is the list concatenation operator, and when we concatenate two lists, we get list as an output, according to ++ definition.

2. Associativity

(xs ++ ys) ++ zs = xs ++ (ys ++ zs), order of evaluation will not change the resulting list

To prove this, we again need to look at ++ definition.

We can use Structural Induction in order to prove associativity.

Base case: If we let x = ys + zs, then [] ++ x = x by definition, LHS equals to x. and for the RHS, we get “” + ys = ys by definition, so ys ++ zs == x, and so LHS = RHS.

Inductive step: Assume that (xs ++ ys) ++ zs = xs ++ (ys ++ zs)

We need to prove that ((x:xs) ++ ys) ++ zs = (x:xs) ++ (ys ++ zs)

LHS: by (*) = (x : (xs ++ ys)) ++ zs => let xs ++ ys = p => x : p ++ zs = x : ((xs ++ ys) ++ zs)

RHS: by (*) = x : (xs ++ (ys ++ zs)) => by assumption => x : ((xs ++ ys) ++ zs)

So we get that LHS = RHS.

3. Identity

The empty list [] is the identity here, because [] ++ ys or ys ++ [] always equals to ys, according to ++ definition (already proved by base case in 2).

Now, we can start playing around with our fold:

*Main> fold [[1,2], [3]] -- per Monoid M

[1,2,3]

*Main> fold [['a'],['b'],['c']] -- same as Monoid M, but operates on set [Char] instead of [Int]

"abc"