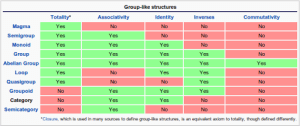

A monoid is an (abstract) algebraic structure. Monoids (and other algebraic structures in general) are useful because they share some set of properties, which then programmers can take for granted.

Let’s give a mathematical definition of what monoids represent, and then we will show some examples.

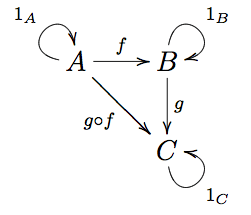

So, a monoid is basically consisted of a set S, along with a binary operation • (note: this doesn’t have to mean multiplication specifically, it can be any operation), so that the following properties are fulfilled:

1. Closure

(∀a,b ∈ S): a•b ∈ S

This basically means that the operation • belongs in the same set as the arguments a and b.

2. Associativity

(∀a,b,c ∈ S): (a•b)•c = a•(b•c)

This means that the order of evaluating expressions will not matter.

3. Identity

(∃e∀a): a•e = e•a = a

For example, the set of natural numbers ℕ together with the binary operation + (standard addition) make up a monoid. Let’s see how:

1. Closure – Every addition of two natural numbers is also a natural number.

2. Associativity – Order of addition will not change the result, i.e. (a+b)+c = a+(b+c)

3. Identity – The identity element of this specific monoid is e=0, because we have that any natural number added to 0, or 0 added to any natural number will be the natural number itself.